Note: This blog article was originally posted here.

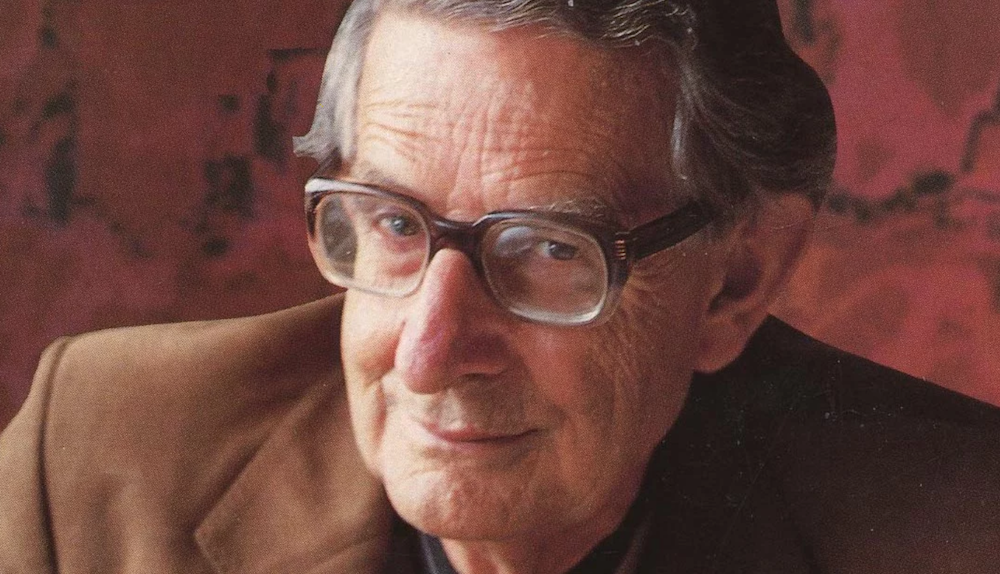

About 65 years ago, German-British psychologist Hans-Jürgen Eysenck (1916-1997) caused a great stir with a paper in which he questioned the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Patients, according to Eysenck, are often better off after some time had passed, even without treatment -psychotherapy is thus ascribed a healing effect that is not caused by it. In short, Eysenck’s assessment was that psychotherapy is ineffective, even preventing improvement in some cases.

Psychotherapy is generally considered an effective procedure

The development of the randomized controlled trial, which compares treated patients with an untreated control group, and meta-analysis, in which many studies are mathematically summarized, attempted to address Eysencks allegation. Since then, on the basis of such methods, there has been a perceived certainty that psychotherapy, in contrast to Eysenck’s allegation, is indeed effective, as a very large decrease in, for example, depressive symptoms has been found in treated versus untreated groups.

Was Eysenck right after all?

A recent paper by Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert (2018) curbs this enthusiasm about meta-analytic findings on the effectiveness of psychotherapy for depression and addresses the question of whether Eysenck might have been right. In particular, the authors argue that much of the evidence on the effectiveness of psychotherapy in depression is distorted by so-called bias, that is systematic errors or artifacts in randomized controlled trials that make the effectiveness of psychotherapy shine in a much brighter light than is actually the case.

Bias can be caused by many factors. When new drugs are developed and evaluated, they are usually compared to a so-called placebo: Patients do not know if they are given a pill with or without an active ingredient. Often, a placebo effect is also found: simply by the fact that patients believe they take an effective drug improves their symptoms, even if it is a sugar pill with no active ingredient.

This placebo effect is also of particular importance for psychotherapy research: Patients in psychotherapy studies know exactly whether they are receiving the therapeutic treatment studied or if they are in the control condition. Because patients in the treatment condition expect an effective treatment, this placebo effect alone could improve their symptoms without the treatment itself being significant. On the other hand, patients in the control group know that they are not expected to see any real improvement, which has a negative effect on the alleviation of their symptoms, as these patients often do not change their behavior until they receive treatment after the study has ended. This is just one of many types of bias that might cause psychotherapy to be considered much more effective than it actually is.

Findings

The study by Cuijpers and colleagues therefore attempted to analyze how the effectiveness of psychotherapy in depression decreases when controlling for all types of bias. It turned out that for all types of psychotherapy the overall effects decreased heavily. The effectiveness of therapies for depression was overestimated for a long time. It turned out, however, that despite the control of all possible systematic errors, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) still yielded positive results. For psychodynamic procedures, this was not the case, although not even all forms of bias could be controlled for. For other procedures, such as interpersonal therapy, there have been too few studies to make accurate statements.

This analysis shows that Eysenck’s verdict must be taken very seriously, albeit being probably incorrect for very well empirically grounded procedures. More accuracy and more precise research methods are needed to truly ensure the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic approaches.

Image Source: Wikimedia